RePercussion Section: Taking Plastics Personally

by Sandra Steingraber, SEHN senior scientist

Last fall, California sued ExxonMobil for lying about plastic.

More specifically, California’s state attorney, Rob Bonta, accused Exxon of carrying out “a decades-long campaign of deception that caused and exacerbated the global plastics pollution crisis.”

At the heart of Exxon’s duplicity, Bonta said in his complaint, is ExxonMobil’s “advanced recycling” technology, which encourages consumers to keep purchasing single-use plastics even as they conscript themselves to dutifully filling up blue boxes with plastic waste every week and trundling them out to the curb. We labor under the belief that we are all collectively engaged in responsible citizenry, helping direct plastic waste into a raw material that can and will be transformed into other useful objects.

Not so, according to the state of California. Instead, virtually all (92 percent) of the plastic waste processed through ExxonMobil’s advanced recycling technology becomes fuel for burning, not recycled plastic commodities.

Further, the plastics that that ExxonMobil’s does produce via advanced recycling contain so little plastic waste that they are effectively virgin plastics misleadingly marketed as “circular,” a word that falsely implies sustainability. In the best-case scenario, “plastics produced through ExxonMobil’s ‘advanced recycling’ program… will only account for less than one percent of ExxonMobil’s total virgin plastic production capacity, which continues to grow.”

Meanwhile, the oceans, our blood, the fish in the oceans, our breastmilk, the birds in the sky, the tea in our cup, the trees in the forest, our testicles and brains, and the undulating bodies of earthworms are all filling up with molecules of plastic. With bad consequences for health, survival, development, and reproduction for everybody, as Ted Schettler outlines in his essay in this newsletter.

Plastics are an existential crisis.

***

If all this sounds familiar, it’s because the language of the California lawsuit against Exxon on plastics reiterates the language of the accusations against Exxon on the climate crisis.

Exxon knew.

Exxon knew decades ago that lighting vast amounts of gas and oil on fire would destabilize Earth’s climate system and lead to devastating consequences for all life forms, including us. But instead of warning the public, they deceived us—along with lawmakers and shareholders—and engaged in a public relations campaign that falsely implied their products were part of a sustainable economy. Exxon denied and misrepresented the climate crisis intentionally, conscious that their products wouldn’t stay profitable once the world knew about the existential risks of fossil fuels.

The difference is in the intimacy quotient. The climate crisis takes place high in the atmosphere, which is slowly being seeded by molecules of invisible heat-trapping greenhouses gases, mostly notably carbon dioxide and methane. And while consequences are highly visible—our city burns down, our house floods, seawater rises through the sewer grates on sunny days, the ice fishing season disappears—the causes are not. Our main visuals of the causes of the climate crisis are charts showing parts per million trends and infographic memes of blue stripes shading into red. The physics and chemistry is all happening way above our heads.

By contrast, the climate crisis’ twin, the plastics crisis, is so personal. The responsible molecules are in our tea bags, our kitchen floors, our kids’ raincoats, our water bottles, our shopping bags, our take-out orders, our microfiber underwear.

If the climate crisis is an aloof serial killer, the plastics crisis is the stalker with boundary issues who knows way too much about you.

***

The plastics crisis doesn’t so much expose your body to toxic substances, it becomes your body.

Like oil, gas, and coal, plastics are also fossils. They are petrochemicals, the polymerized molecules of once living things, mostly tiny sea creatures from the Devonian Era. Plastics are just similar enough to us to be biological reactive—mimicking hormones, or disrupting heart rhythms, altering lipid metabolism, silencing or amplifying the activity of various genes—but just different enough that living things do not possess the enzymes to break them apart.

Hence, plastics just don’t go away. And as plastic particles get smaller and smaller over time, they get more and more dangerous. They can slip past the membranes of the alveoli in our lungs and enter our bloodstream. They can pass through the blood-brain barrier.

As Ted Schettler reminds us in his accompanying essay, microplastics are, by definition, smaller than 5 millimeters. Five millimeters is roughly the size of a pencil-top eraser. But nanoplastics are, by definition, less than a micrometer, and a micrometer is a thousand times smaller than a millimeter.

One micrometer is roughly the size of E. coli —that rod-shaped fecal-oral bacteria responsible for food contamination incidents and product recalls. The body of a single E. coli bacterium is ten times smaller than the average human cell. Nanoplastic particles are smaller even than the food poisoning bugs.

Nanoplastics inhabit our most intimate cellular spaces.

***

In a new paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an interdisciplinary research team led by economist Maureen Cooper from University of Maryland and Phil Landrigan, who directs Boston College’s Global Observatory on Planetary Health, looked at the hazards to human health caused by plastics.

Specifically, the team examined the disease burdens of just three common plastic chemicals: bisphenol A (BPA), DEHP, and PBDEs. They found that BPA was, in 2015, associated with 5.4 million cases of heart disease and 346,000 strokes while DEHP caused 164,000 deaths among 55-64 year-olds. Eliminating exposures just to BPA and DEHP alone would have prevented 600,000 deaths in one year.

Meanwhile, PBDEs “contributed to a loss of 11.7 million IQ points in children.”

Plastics are personal.

***

In January 2025, ExxonMobil countersued California state attorney Rob Bonta for defamation. The company claimed Bonta had falsely accused the company of falsely informing public about the recycling of plastic.

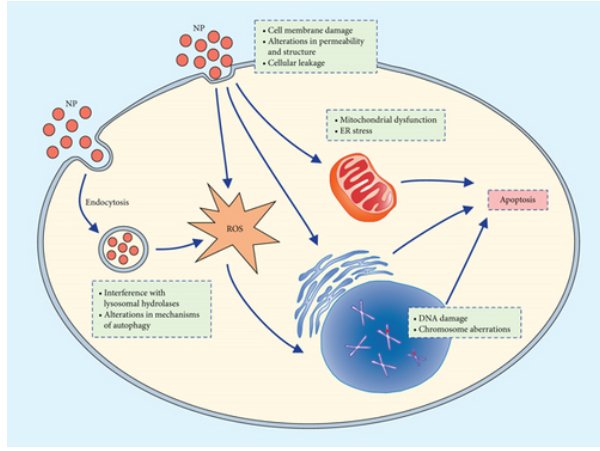

Nanoplastic particles taking up residence inside the cells of our bodies. Once inside, they can activate oxidative stress pathways, damage DNA, disrupt the activity of enzymes, chemically degrade lipids, and otherwise tinker with the workings of our organelles. From N. Joksimovic et al, Nanoplastics as an Invisible Threat to Humans and the Environment, Journal of Nanomaterials, 2022.