Incorporating the Best Available Science in Chemical Regulation: We Should Not Expect Less

SEHN’s science director, Ted Schettler, MD, MPH, is part of an interdisciplinary group of experts recommending specific improvements in how science is used to prevent harmful chemical exposures and to strengthen the current chemical regulatory processes. Five open-access academic papers, including one which puts forth an overarching consensus statement, together with lay summaries and infographics, create a springboard for action. The Networker’s editor, Carmi Orenstein, speaks with Ted about his involvement with this vital, expansive effort, and his thoughts about what is possible in moving forward chemicals policy.

Editor: Ted, your influential work on chemicals and health goes back decades. The papers resulting from this new effort reflect evolving ways of thinking about human health and the environment, now well recognized within the scientific and public health communities, but often poorly integrated into policies and practices. These include the different ways chemical exposures impact different people and populations, how to effectively address the hundreds of thousands of chemicals and chemical mixtures in use, and better understanding exposure levels that can result in a diverse range of health impacts. What are some examples of how these papers reflect this evolution?

Ted: This project brought together toxicologists, epidemiologists, and others from academia, the non-profit sector, and government representatives who have expertise in evaluating and understanding health risks associated with chemical exposures in the real world. We thought that identifying some of the basic shortcomings of chemical safety evaluations by regulatory agencies and product manufacturers in the United States, along with providing policy recommendations, could spark efforts to address those deficiencies and improve health protection.

It’s important to recognize that regulation of chemicals in the United States is spread across various agencies. Their legislative mandates and approaches differ. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates pharmaceuticals and requires extensive safety assessments before a new drug is considered for the market. The FDA also regulates cosmetic ingredients, but their oversight of those chemicals is far less rigorous. One division of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for regulating pesticides and is supposed to require a battery of studies performed in prescribed ways in order to evaluate their potential toxicity. But the agency not infrequently waives those requirements, allowing inadequately studied pesticides onto the market. Another division of the EPA regulates chemicals used in industrial processes or various consumer products. Some of these chemicals show up in communities as drinking water contaminants and air pollutants. By law, the EPA is supposed to use the best available science when performing chemical safety and risk evaluations. Our project calls out and updates some of the important ways that regulatory agencies and businesses making materials and products could improve their risk evaluations and decision-making by using updated approaches that incorporate the best available science. We should not expect less.

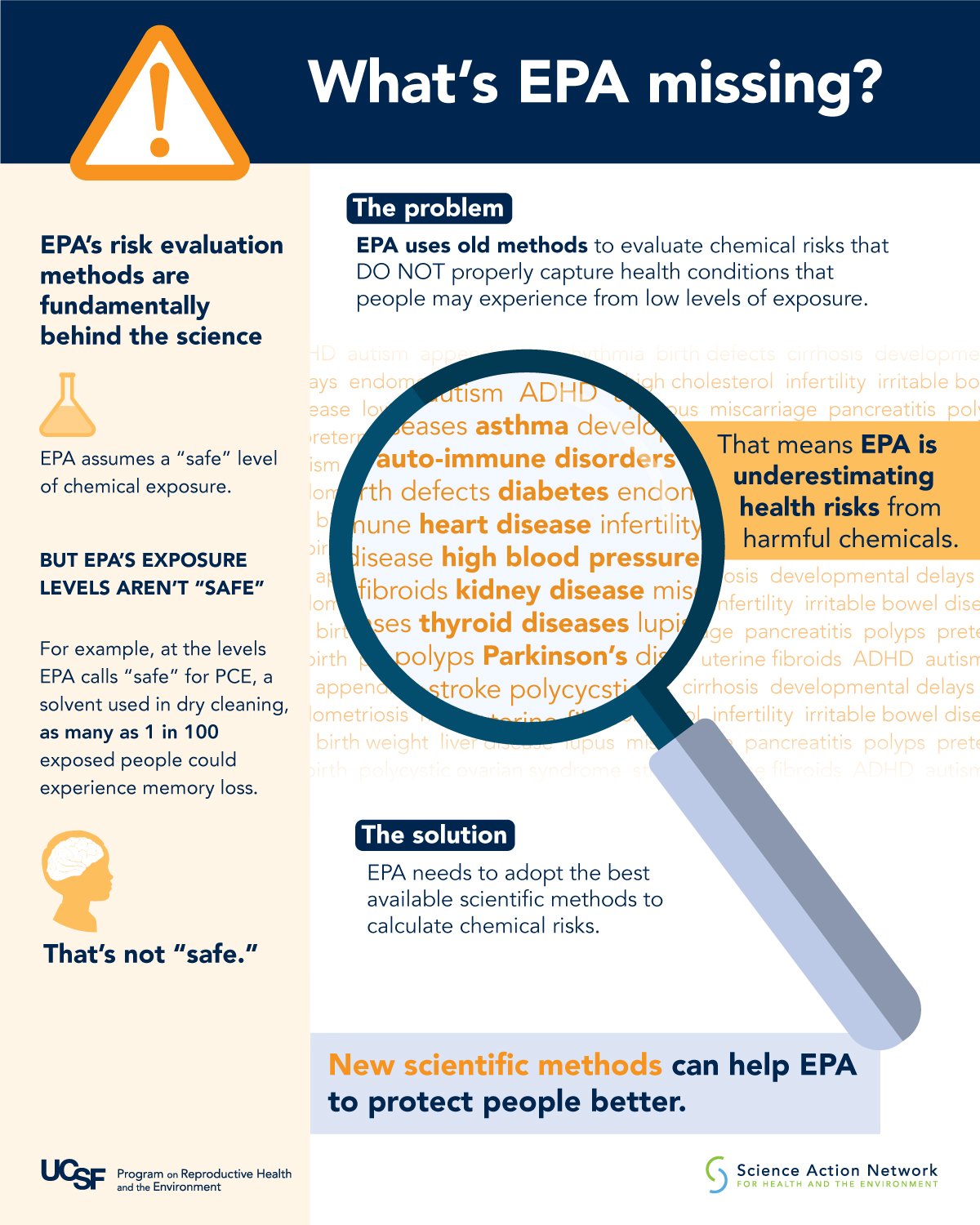

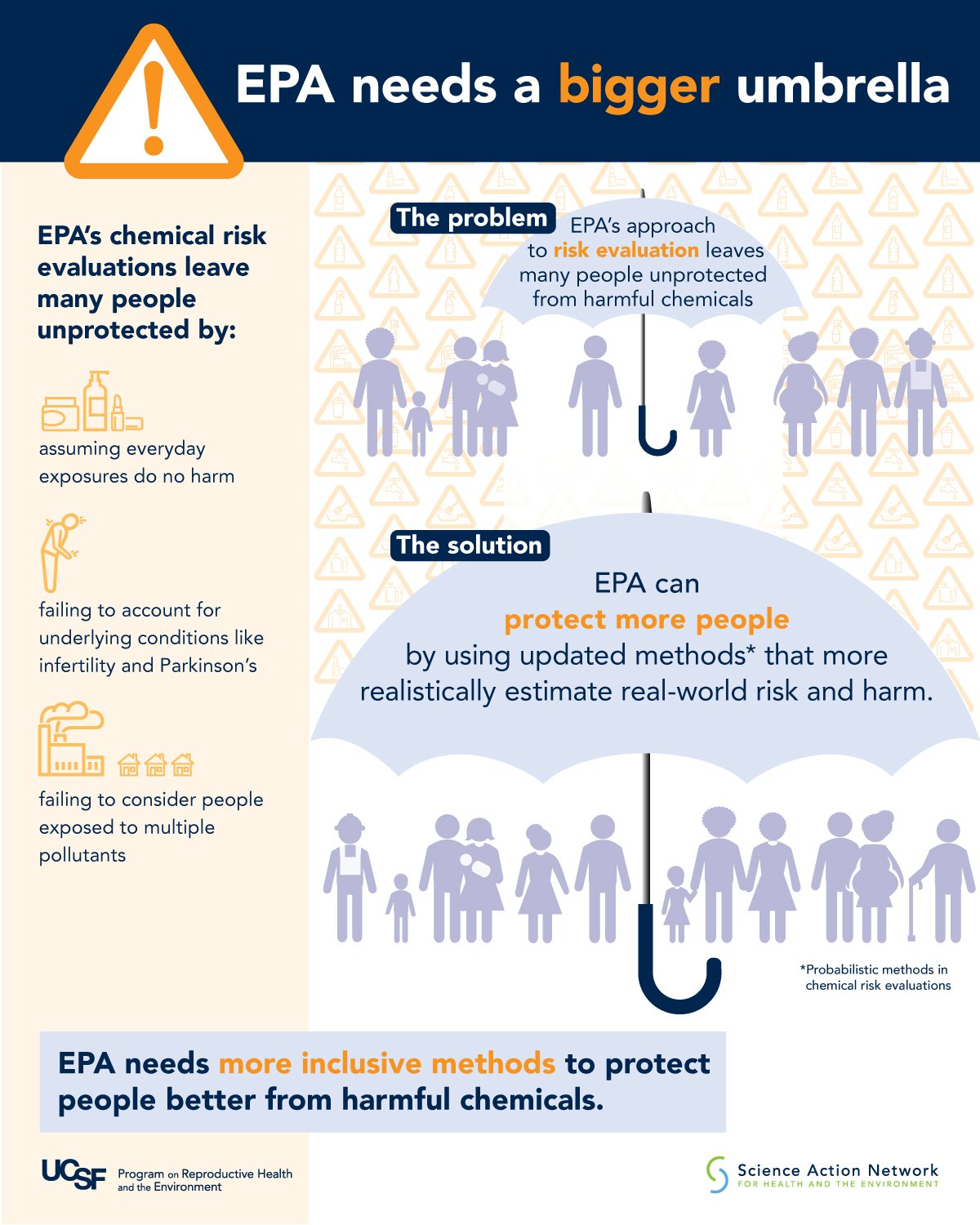

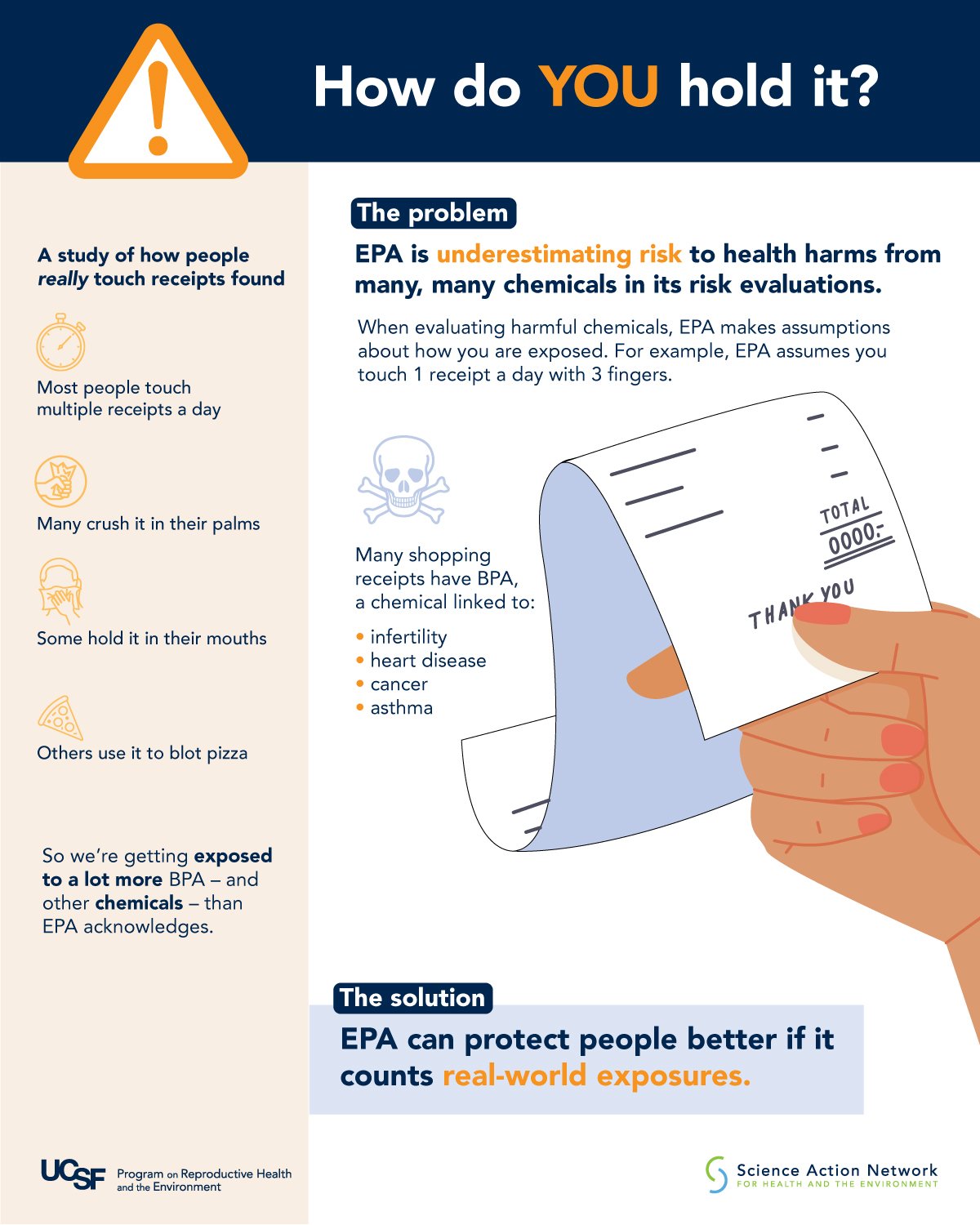

Here are a few examples. A common practice for evaluating potential non-cancer health effects of a particular chemical—like asthma, birth defects, neurodevelopmental disorders, among others—assumes a safe human exposure level below which these impacts will not occur. Then the agency sets out to estimate what that level is, usually based on laboratory animal studies and sometimes on epidemiologic data as well. One of the new papers persuasively challenges the assumption of a “safe” exposure level for non-cancer effects of a given chemical and recommends an alternative approach, based on the reality that many people are already chronically exposed to that or similar chemicals or that they have health conditions making them vulnerable to far lower doses.

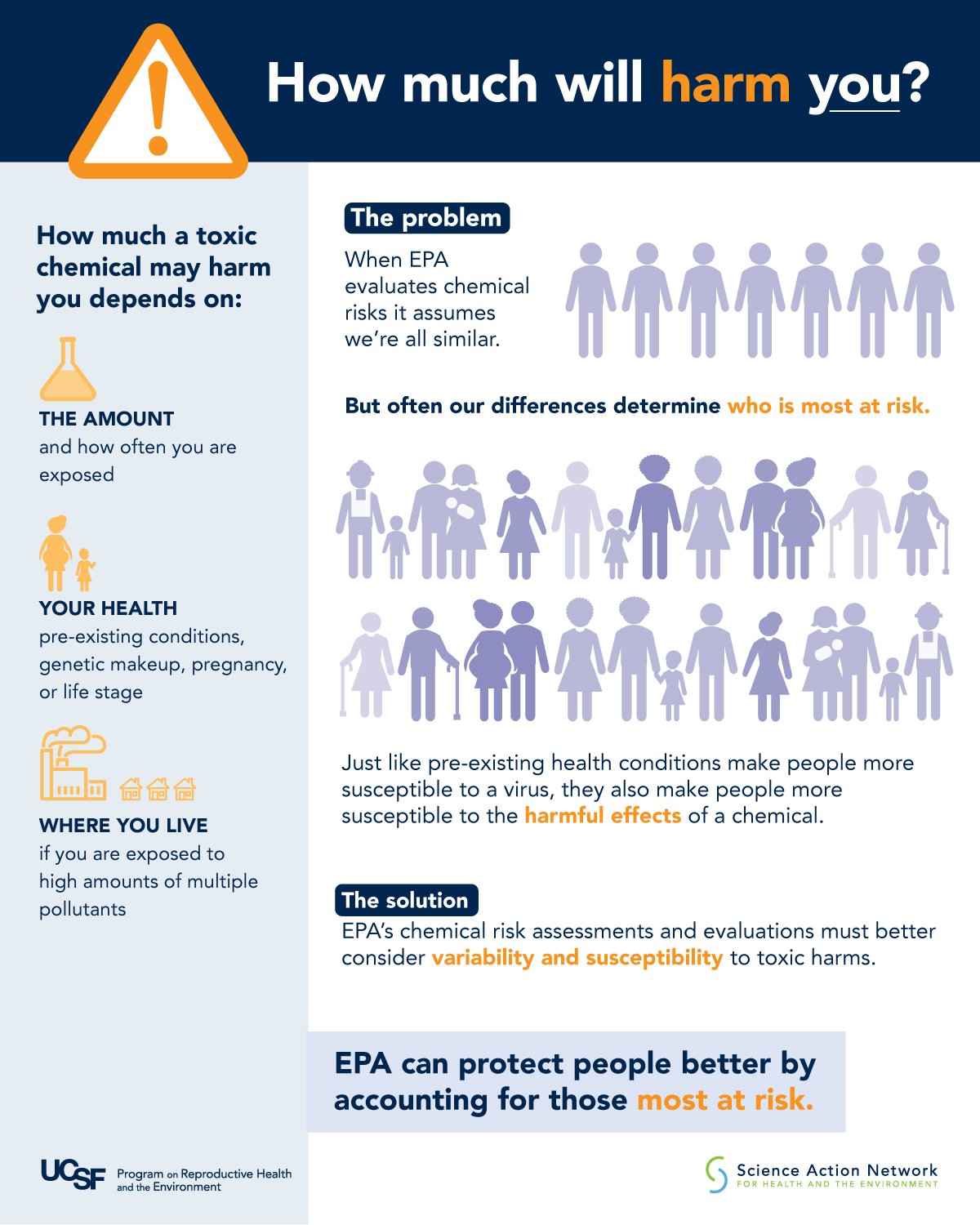

Another paper recognizes the marked variability in susceptibility to harm from chemical exposures in the general population due to age, health status, gender, occupation, social and neighborhood factors, and concomitant exposures, among other factors. The authors recommend using updated methods and data to incorporate consideration of human variability and susceptibility in risk assessments, including the use of more realistic and health-protective adjustment factors.

A final example is the paper exploring the rationale and opportunities for regulating certain chemicals by groups or class. As it is now, the EPA addresses one chemical at a time in its chemical regulatory program authorized by the Toxics Substances Control Act. As a result, thousands of chemicals in commerce remain unevaluated because of time and resource constraints. In addition, if a chemical on the market is determined to present an unreasonable risk of harm, there is nothing to stop a manufacturer of a product containing that chemical from simply substituting a similar but untested chemical, buying time until the substitute comes under closer scrutiny. If chemicals with similar structures or other properties were addressed in groups, these shortcomings could be reduced or eliminated. The authors suggest using a decision-tree approach enabling grouping chemicals for evaluation for regulatory or other purposes.

Editor: How do you feel about the state of the science on these questions? Would you have imagined being further along by now—in other words, are there still substantial knowledge gaps? Or, do you think that, for the chemicals and chemical classes of concern, we have more than enough to data to create sound policy?

Ted: The state of the science on these issues is far ahead of what is actually being used by regulators in the United States. In fact, many of the policy recommendations in this series of papers were suggested in a 2009 publication by the National Research Council of the National Academies of Science called Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment. We used this as an opportunity to update those recommendations with even more recent information. There will always be knowledge gaps. Unfortunately, uncertainties are often used to allow ongoing exposures while manufacturers and others call for more research. That can go on for years.

Editor: The very first principle and recommendation of the consensus statement addresses what many would consider a profound injustice in chemicals policy: where the financial burden of data generation lies. “The financial burden of data generation for any given chemical on (or to be introduced to) the market should be on the chemical producers that benefit from their production and use.” Can you tell us why, for this group of authors, this rose to the top? Related, how does this interact with the problems associated with industry-sponsored research?

Ted: With the exception of pharmaceuticals and pesticides, under most US laws the onus is on the government to identify and request data from the industry and to evaluate potential chemical toxicity. This requires considerable government time and resources—public money.

We and many others conclude that the financial burden of data generation should be on the chemical producers. Moreover, these data should be publicly available for evaluation as well.

As your question suggests, this does raise the question of the validity of industry-sponsored research. Whereas that is, of course, a potential problem, if the data are open to public as well as regulatory agency scrutiny, study design, strengths and weaknesses, and data interpretation can be evaluated. Studies are also subject to replication and inconsistencies revealed.

Editor: The initiative is coupled with summaries, infographics (included here; click through them below), and blog posts accessible to lay people, housed on the website of the University of California San Francisco’s Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment. What are some ways different types of people—medical professionals, public health professionals, community leaders, and the lay public—can work with this information? Should elected officials be a key target audience, given the changes in policy making that are recommended and the champions in government that will require?

Ted: Medical professionals often have minimal training in environmental health. This information can help them to respond to questions they often confront in their clinical practice and validate concerns expressed by their patients. People living in communities with hazardous air pollutants or contaminated drinking water are often told that their exposure levels are “safe,” so not to worry. Yet they feel sick, see excessive illness in family members and friends, or are concerned about long-term impacts. These papers make clear that we need to improve the process by which we evaluate chemical safety and medical professionals can become powerful voices for supporting those efforts. Similarly, public health officials can use this information to establish more health protective policies and practices in the communities they serve, and advocate for more systematic changes.

Entire classes of some chemicals can and should be avoided because of toxicity concerns. Businesses can use this information to align their purchasing and manufacturing decisions with the best, most protective practices. If a business does create their products from safer materials, it can publicize that fact, and may increase their market share. The general public can aim to avoid buying products with inadequately evaluated chemical ingredients or products containing any member of a class of chemicals in which only a handful have been tested and shown to be hazardous as used. We should assume that other members of the class are also hazardous unless studies ultimately show otherwise. A good example of that is the extremely large group of chemicals known as perfluorinated alkyl substances or PFAS. These are the non-stick, water- and grease-proofing chemicals that have been much in the news lately because they are highly persistent and contaminate drinking water throughout many areas of the United States. All members of this class should be avoided except for “essential” uses. We will never have the time or resources to evaluate each of these thousands of PFAS chemicals individually.

And, yes, elected government officials, government agencies, and their staffs can and should use this information to enact more health protective policies and practices. It’s important to note that existing laws and regulations already allow implementation of many of the recommendations contained in each of these papers. Some state governments have enacted more protective chemical policies than the federal government, resulting in a patchwork of regulations in various areas of the country.

Editor: The infographics include statements on what the EPA can and should do, such as, “EPA can protect people better by accounting for those most at risk.” These statements reflect the full papers’ principles and recommendations for health-protective chemical policies and regulations. How does this ambition—putting forward the ways that the EPA and other agencies need to actually change—interact with what we know about the state of the EPA right now? For example, the recent New York Times piece, “Depleted Under Trump, a ‘Traumatized’ E.P.A. Struggles With Its Mission” says,

The nation’s top environmental agency is still reeling from the exodus of more than 1,200 scientists and policy experts during the Trump administration. The chemicals chief said her staff can’t keep up with a mounting workload….

Michal Freedhoff, who leads the E.P.A.’s chemical unit, told Congress recently that the office of chemical safety would fall short of its obligations and miss many “significant statutory deadlines.” She blamed the fact that after a 2016 law significantly increased the agency’s duties, the E.P.A. under the Trump administration never sought the resources from Congress that were required to perform the work.

Another recent investigative, piece, Why the U.S. Is Losing the Fight to Ban Toxic Chemicals, says, “the flaws of the American chemical regulatory apparatus run deeper than funding or the decisions of the last presidential administration.” It outlines the ways the chemical industry has long enjoyed deep influence in chemicals regulation policy and stages resistance for each attempt to move a chemical through the regulatory process. Do you see openings for turning around this status quo?

Ted: Without question the EPA is strongly influenced by the regulated community and that influence has increased over the last 35 or more years. It varies to some extent from one administration to the next, depending on which party controls the White House and Congress. The Reagan Administration combined vigorous deregulation of industry with severe budget and staff cuts. The George W. Bush Administration undermined science-based policy. The Trump Administration did both—it severely cut EPA staff and budget and simply ignored some science-based policy decisions required by law and regulations. A large number of well-qualified career scientists left the agency and replacing them will not be easy.

During this time some state legislatures and regulatory agencies—for example California, Washington, and Maine, among others—have been much more forthright in adopting health-protective chemical regulatory policies and practices in certain instances that reflect some of the recommendations in these papers. Often those advances are directly traceable to successful, long-term advocacy campaigns led by non-governmental organizations. Other states—for example, Louisiana and Texas—reject increased regulatory oversight of their oil, gas, and chemical industries. Residents in disproportionately affected, overburdened communities pay for that with their poor health. These environmental injustices must be addressed within the regulatory framework.

Hundreds of progressive businesses are not waiting for regulations to drive their manufacturing and purchasing decisions. They see good business opportunities in being able to demonstrate their interest in producing safer materials and products by reducing utilization of hazardous chemicals. Market-based campaigns organized by various organizations encourage these shifts.

We’re seeing the current EPA struggle with the staff and budget cuts of recent years but yet, as noted previously, current laws and regulations permit the adoption of many of the recommendations in this series of papers. Time will tell if agency leadership has the capacity and political will to utilize the best available science to protect the public’s health throughout the country, including in our most vulnerable communities.

Editor: How did this extraordinary group of co-authors come together, and what are its next steps? Aside from your co-authorship on the consensus statement paper, you co-authored “Advancing the science on chemical classes,” a research area in which you’ve devoted much effort. The paper puts forward the “decision tree approach” you mentioned above for enabling the assignment of any chemical to a chemical class, and thereby accelerating the process by which protective rules can be established. (See the blog post summarizing this paper here.) What are the next steps toward making this approach a reality?

Ted: I was a member of an advisory committee convened by staff at the Program for Reproductive Health and Environment (PRHE) at UCSF that recommended the topics for this series of papers, based on where we saw deficiencies in risk evaluation of chemicals that are ripe for action. PRHE then gathered the larger group of co-authors with expertise in those particular areas. Since its inception, PRHE has combined a rigorous scientific research agenda with policy advocacy and education bringing together a diverse group of national and international scientists and public health advocates who regularly meet to explore a wide range of environmental health issues. We intend to continue outreach efforts to promote the recommendations in these papers.

With regard to advancing the science on chemical classes, we can see some progress but there is still a long way to go. The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) convened an expert committee in 2008 that addressed the cumulative risk of exposure to a group of chemicals called ortho-phthalates, based on common adverse health effects. Another NAS committee considered the validity of regulating halogenated flame retardants as an entire class. In their final report they discussed various ways that chemicals can be grouped for analysis and policy decisions. The Consumer Products Safety Commission banned a group of phthalates from children’s toys, based on common mechanisms of toxicity and adverse health outcomes. But these same phthalates remain present in other consumer products and exposures remain widespread. We’re seeing growing advocacy for restricting the thousands of PFAS chemicals from all but essential uses because they are highly persistent in the environment, extremely difficult to remove from drinking water and food sources, toxic, and exposures are virtually ubiquitous in the entire population. The Toxics Substances Control Act, as written, already empowers the EPA to regulate certain kinds of chemicals as a class, based on various criteria, if the agency articulates the rationale and chooses to do so.

Advocacy-driven market-based campaigns have been increasingly successful in persuading product manufacturers to avoid using any members of various classes of chemicals based on known or presumed similarities in toxicity, environmental persistence, or bioaccumulation potential. This approach helps to generate a business-case for switching to safer alternatives, even in the absence of stricter federal regulation. I’m hopeful that these developments will help push regulators, chemical and product manufacturers, and purchasers toward considering the safety of classes of chemicals when making decisions. But it’s going to require a concerted effort to make significant additional progress. The chemical industry predictably pushes back against this more efficient and health-protective approach to regulation, with an eye toward protecting members of large groups of chemicals from scrutiny and potential restrictions.

*Created by the UCSF Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment and the EaRTH Center on behalf of the Science Action Network