|

Dear friends,

Last May, I ascended the summit of Hawk Mountain, an officially designated sanctuary for raptors along the Appalachian flyway in Berks County, Pennsylvania. I had come on official business. Asked by the Library of America to edit a new, endowed, and definitive collection of Rachel Carson’s oceanographic writings, I wanted to retrace Carson’s steps to the north overlook where she had hiked many times to witness the annual fall migration of hawks and eagles.

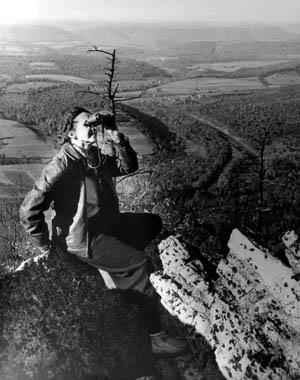

In fact, I had come seeking a specific rock on that summit. It was the sharply angled chunk of limestone that Carson had straddled when, in October 1945, her companion Shirley Briggs had snapped a photograph of the soon-to-be famous marine biologist and environmental author scanning the horizon with her leather-strapped binoculars.

I particularly love that photograph of Carson because—unlike her later publicity and media photos, in which she appears as prim, formal, reserved, and a little awkward, as women scientists in the mid-20th century were required to be—the Hawk Mountain photo reveals a beautiful, self-possessed woman entirely at ease in the natural world, her bad-ass leather jacket flung open to the wind. I particularly love that photograph of Carson because—unlike her later publicity and media photos, in which she appears as prim, formal, reserved, and a little awkward, as women scientists in the mid-20th century were required to be—the Hawk Mountain photo reveals a beautiful, self-possessed woman entirely at ease in the natural world, her bad-ass leather jacket flung open to the wind.

Friends, I think I found the rock. It sure seemed to match the contours of the one in the photo that I had pulled up on my cell phone. And the geographic features of the river valley below also lined up.

And so, I sat on a mountaintop on a rock that I fully believed was the rock, and re-read, for purposes of inspiration, Carson’s field notes that she had written in this very spot 76 years earlier. They reveal that she had climbed up here not solely to tabulate the number of hawks flying by:

As always in these Appalachian highlands there are reminders of these ancient seas that more than once lay over all this land. . . . these whitened limestone rocks on which I am sitting—these, too, were formed under that Paleozoic ocean, of the myriad tiny skeletons of creatures that drifted in its waters. Now I lie back with half closed eyes and try to realize that I am at the bottom of another ocean—an ocean of air on which the hawks are sailing.

Rachel Carson sat astride a mountaintop and ecstatically imagined herself at the bottom of the sea that made the mountain. She was the master of the deep-time view.

But there is another point to this story. Not only did this pilgrimage to the top of Hawk Mountain help inspire and prepare me to compile and introduce Carson’s collection of sea writings—released this month by Library of America—it helped inspire and prepare me for my current work.

Last May when I climbed Hawk Mountain, I had made the big decision—having been inside the classroom since age 5—to leave academia, and I was about to assume a post as senior scientist at the Science and Environmental Health Network (SEHN).

In making this leap, I knew I could better serve the world. I knew I would be joining a whole team of legal and scientific experts with deep-time views who were dedicated to Rachel Carson’s idea that the right to a safe environment is a human right.

And its corollaries: that we have a right to know about toxic chemicals trespassing, without our consent, into our shared environment. That, once knowing, we have an obligation to action. That this obligation to action is a sacred duty that we owe to future generations.

These are all Rachel Carson’s ideas, and they, very intentionally, form the foundation and the vision of SEHN, which serves communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis and its sidecar, the petrochemical pollution crisis.

I am very happy to let you know that, in moving my own scientific research, writing, and advocacy into SEHN, I have found my rock on the mountaintop.

And this is my very personal way of asking you for your support. I invite you to continue Rachel Carson’s legacy by making a financial contribution to SEHN.

At SEHN we are bringing forth rigorous science and legal tools, shaped by ethics, that address environmental health problems that grassroots groups bring to us—fracking operations, new pipelines, contaminated sites, and, mostly recently, carbon capture and storage boondoggles, which make local air pollution worse even as they fail to make the climate crisis better.

To that end, I have joyfully set aside a couple of boxfuls of the Library of America edition of Rachel Carson’s sea trilogy to send donors to SEHN. As thanks for your donation of $250.00 (or more)—or if you sign up to give a monthly donation of $25.00 (or more)—I will sign a copy and send it to you, an exchange that also represents my great thanks for being part of this most amazing collaboration of knowledge, action, and ethics.

Thank you for the many ways you make the world a better place—a place of beauty, kindness, health, and justice.

Unfractured,

Sandra Steingraber, PhD

Senior Scientist, Science and Environmental Health Network

|